Context

The ability to understand user context is increasing continuously. New sensors and data points colour ever more detail into the picture of who a user is, what they’re doing and where they are interacting with digital services.

The way in which design responds to context, however, lags this new availability of contextual data points. This is due partly to the relative complexity of creating contextually responsive digital experiences and partly to a misconception among designers that users are willing to change their context in order to gain access to particular products. In reality, such life altering products are few and far between. Most experiences, and particularly those distributed across multiple digital touchpoints, can be made better by embracing contextually responsive principles.

Responsive design is understood today as the ability for digital services to adapt their look, and sometimes their content, to match the display capabilities of the user’s access device. Simple as that may sound, the best examples remain remarkably complex to achieve, but should also be recognised as merely a first step towards much broader potential for adapting design in response to context.

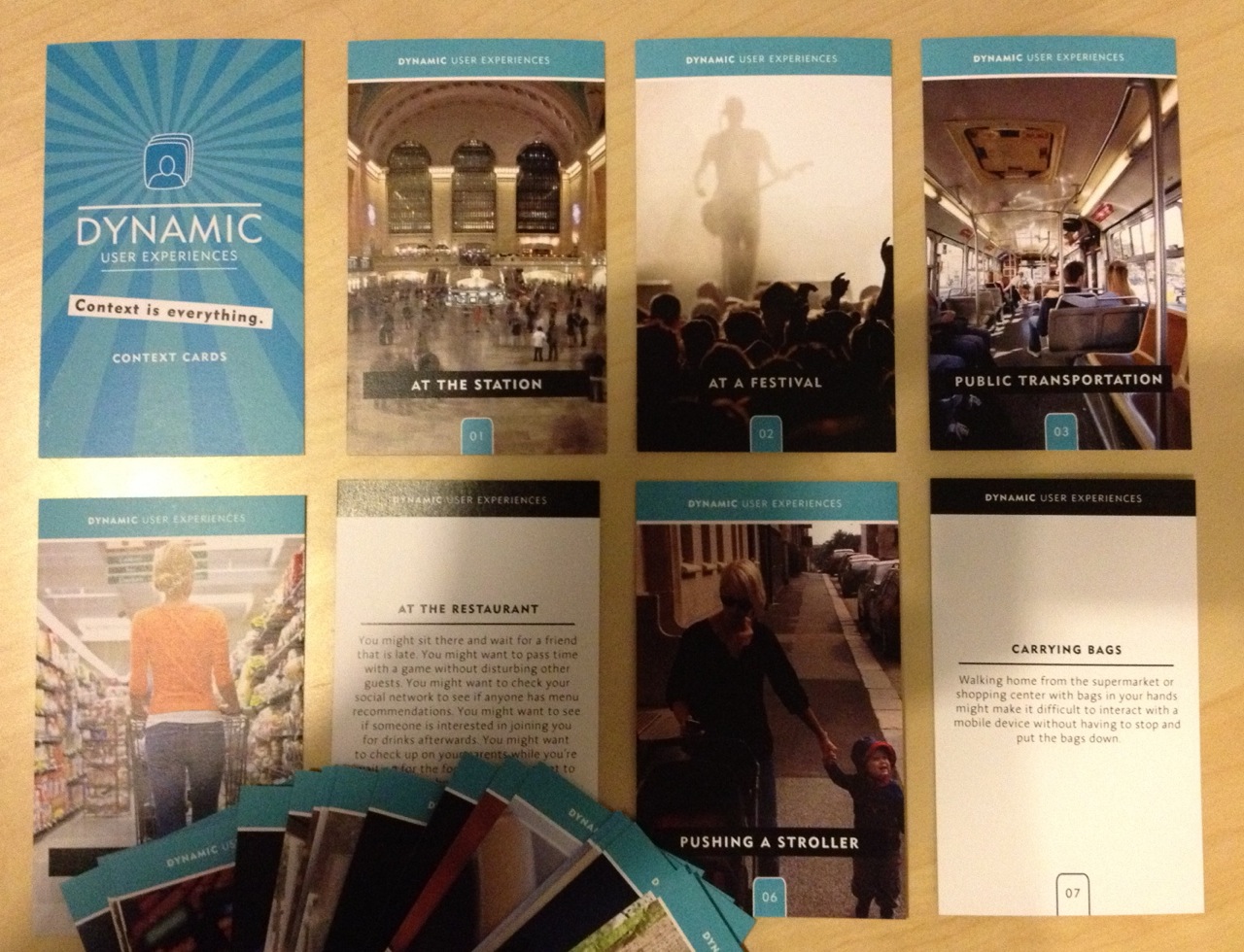

Display capability is just one factor which might influence the way a service manifests to users, but there are myriad others:

- Location

- Light

- Proximity

- Time

- Motion

- Sound

- Temperature

- Tools

- Connectivity

The usefulness of each element is determined by how well a designer translates sensor data into a response meaningful to the user. For instance, a string of GPS co-ordinates accurately reveals where a user is on the surface of the earth, but nothing about what that location means to the user.

However, other data could be combined with GPS co-ordinates to make a contextual assumption about the user’s needs. The service could pull a location-based picture count from Flickr and, if the user was in a place where a particularly high number of photographs had been taken by others, it would be reasonable to assume they are standing close to a sight-seeing attraction. The service could, therefore, prioritise the camera app icon over others, adding it to the lockscreen or making it appear larger than other icons in the menu.

Another obvious example concerns light. Most navigation services offer at least two colour schemes, one suited for daylight and another with more muted tones for the night. Few currently switch automatically between these modes, but there are numerous contextual clues which could be used to determine if it was appropriate to make an automatic switch.

Many devices are now equipped with embedded light sensors; however, data exists to help even those which aren’t to make the same contextual judgements. It would be a simple matter to pull sunrise and sunset times from a web API or, as devices gain closer integration with cars, to activate night mode on the device at the same time as it is activated on the car dashboard.

The complexity of responding to context increases with the number of data points used to inform contextual decisions. It is complex enough to achieve a success within a single dimension, such as ensuring a service looks visually correct within the display limitations of a user’s device. To achieve success across multiple dimensions of context is, using today’s methods, orders of magnitude more difficult. It also carries the risk of trying too hard and ending up with an experience where the user feels the design is doing too much to ‘second guess’ their needs.

However, the rewards make it worth trying. Contextual response improves the usability of existing services, but also holds the possibility of developing entirely new experiences.

Achieving success is more likely when designers take a modular approach to creating service elements. The practical steps required vary considerably depending on the type of service; they are as diverse as the huge range of service experiences enabled by mobile technology. With no set formula or process, how deeply a ‘modular mindset’ is embedded in the development team becomes more important than following a prescriptive framework.

Content, interactions, business logic and any other elements which comprise a service should be made accessible in their most basic forms. By making each element distinct, designers gain flexibility to adjust the way components work together to respond to certain contexts. Not all of these need be used today, but there is an opportunity to ‘future proof’ against further improvements in contextual understanding by taking modularity to an extreme. When a new contextual data point becomes available, the service architecture will be able to respond.

New dimensions to contextual understanding continue to emerge and the pace at which they become available will only increase. However, the first rule of contextual response will never change: the ease with which the user can correct the mistakes of the ‘guessing engine’ will always be as important as the quality of the engine itself. No matter how detailed the data, no matter how many dimensions of context it spans and no matter how regular the user’s behaviour, it is impossible to get it right every time.

Unless the user has a simple way to correct these mistakes – and feels the engine is learning when they do so – they will quickly disable any contextual capabilities, or abandon the service entirely. You need only look to traditional, person-to-person customer service scenarios to understand why: it is frustrating when users feel the customer service representative doesn’t understand them, but even more infuriating when they don’t listen to and remember the user’s corrections.

The predictive text and auto-correct engines essential to typing on cramped touchscreens provide an example. The majority of users report higher satisfaction with engines that are less accurate, but easy to manually correct, than engines with higher accuracy but which make manual intervention more difficult.

The need to feel in control of manual intervention closely mirrors the way users feel about privacy. The benefits of contextually responsive services must be clear and significant to overcome the wariness users feel about sharing the data which enable contextual experiences. On balance, most prefer not to try at all if the potential benefit is marginal. This kind of irrational fear (and the majority of users freely admit it is irrational) is the most immediate stumbling block to widespread adoption.

By clearing explaining the benefits and pre-empting concerns over risk, users can be persuaded to try new things. However, ‘contextual response’ as a concept means little to a customer. It is more effectively presented as an integrated part of an overall service offering. In the visual example above, where the colours used by a navigation service would change automatically, a simple and direct marketing story about ‘Night Mode’ would be more effective than, for instance, asking users “Would you like to share location and light sensor data with this app?”

The starting point for successful contextual response is a mindset which prioritises modularity in all aspects of the service architecture. Subsequent results depend on how effectively user research is used to determine which service elements can be improved through contextual response. And, ultimately, ensuring the service learns from its inevitable mistakes and the user remains in control throughout will ensure good experience.

‘Context’ is in development as a MEX Pathway and will be explored extensively in the coming months, including at the next MEX event. I’d love to hear from those working in this area – please get in touch to share ideas.

“Context” – one of my favourite topics! And one of the main challenges facing us to bring personal mobility, Augmented Reality and “Cloud Connected Me” into day to day lifestyle of the average consumer.

Note the quote, “Content is King, but Context is Queen” in the summary article from The AR Summit which I chaired a few weeks ago.

http://bit.ly/ARSummit-MM1

Further expanded on in my intro to the conference

http://bit.ly/ARSummit-KSBIntro

One of the most important enablers of consumer value and delight. Also a key value proposition for personalisation of advertising.

You are right on target with this area of concentration!

[…] The exploration of these themes has already begun in an earlier essay entitled ‘Context‘. […]

[…] essays builds on my original article, ‘Context‘, published in April […]